The 21st century will be marked as an era of unprecedented global integration. In fact, the economies of most nations are so interconnected that nowadays the notion of autarky seems idealistic and perhaps even laughable. Globalisation is nonetheless a polarising issue, the pros and cons of which have been thoroughly discussed in textbooks, and perhaps less thoroughly antagonised by certain political figures. Arguably, a more interesting question to ask is why globalisation occurred, and what catalysed the deep integration of our economies. The rise in globalisation tends to be attributed to improvements in technology, a general shift towards more free-market and free-trade policies, and the acceleration of economic growth, especially in Asia. However, mainstream discourse largely ignores a controversial and phantom factor in the globalisation story: offshore financial centres (OFCs).

Corporations are said to be the biggest benefactors and participants of global trade. In fact, an estimated 60% of all cross-border trade actually happens as internal company trade, rather than 2 unrelated entities trading with each other, according to an OECD report from 2002. For this reason, it is not unusual for multinational enterprises (MNEs) to have branches and legal entities incorporated in different countries where they are doing business. The global brewing giant Anheuser-Busch InBev for example, is said to have at least 680 corporate entities incorporated in around the 60 countries they have a presence in. For MNE’s such internationally spread out and complex corporate structures are rather common and serve very specific business purposes.

Firstly, complex and internationally spread-out corporate structures help increase the competitive advantage of firms by lowering their costs through minimization of their tax bill and regulatory arbitrage. Popular destinations are the Cayman Islands, the British Virgin Islands, Bermuda amongst others, thanks to their low tax rates and limited regulatory requirements. These jurisdictions tend to be referred to as Offshore Financial Centres (OFCs).

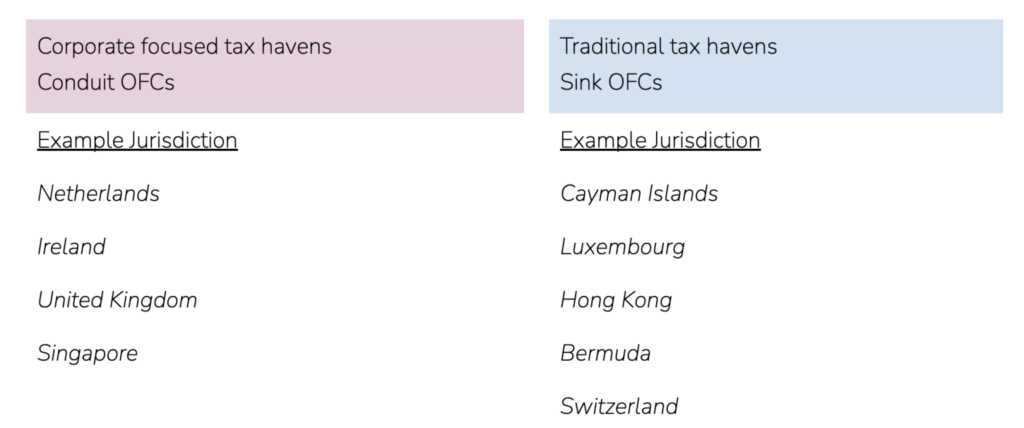

Academic research tends to distinguish OFCs based on their role, and classify them as Sink OFCs or Conduit OFCs, with the latter being corporate-oriented tax havens while the former is related to the traditional tax haven definition.

In essence, corporate tax havens (Conduit OFCs) are used to channel funds from high tax jurisdictions to traditional tax haven destinations (Sink OFCs) where tax exposure is far smaller. Conduit OFCs are also very relevant when it comes to taxation and valuation of intangible assets such as copyrights and intellectual property. The Dutch Sandwich and Double Irish arrangements are good examples of this, and on their own are substantially complex and require an article or two to cover.

Conduit OFCs tend to be well-governed nations with very favourable “holding company regimes”. This could entail no withholding taxes, foreign dividends being exempt from taxation, favourable tax treatment of intellectual property, flexible corporate tax rates, a high amount of bilateral tax treaties, low costs of incorporation and advanced financial systems and infrastructure. The Netherlands is a good example of a Conduit OFC. The nation is one the most attractive destinations for incorporations of holdings due to their tax efficiency, flexibility of domestic corporate and tax laws, and ability to easily provide easy exit routes for profits of subsidiaries. For example, whether you have direct ownership of a subsidiary or own it through a corporate structure, once profits are repatriated, local tax agencies could require you to pay taxes on said income. However, due to tax treaties in place, the tax exposure in the “home” country is likely to be significantly diminished. Furthermore, a Dutch holding company can furthermore reduce tax by creating a very real (legal) possibility to defer and perhaps even avoid taxation in the “home” country.

Sink OFCs tend to be jurisdictions with a disproportionate amount of wealth relative to the size of industry and population. And hence, perhaps unsurprisingly, when looking at nations with the largest GDP per capita, almost all in the top 15 are tax havens, once oil and gas-rich nations are excluded.

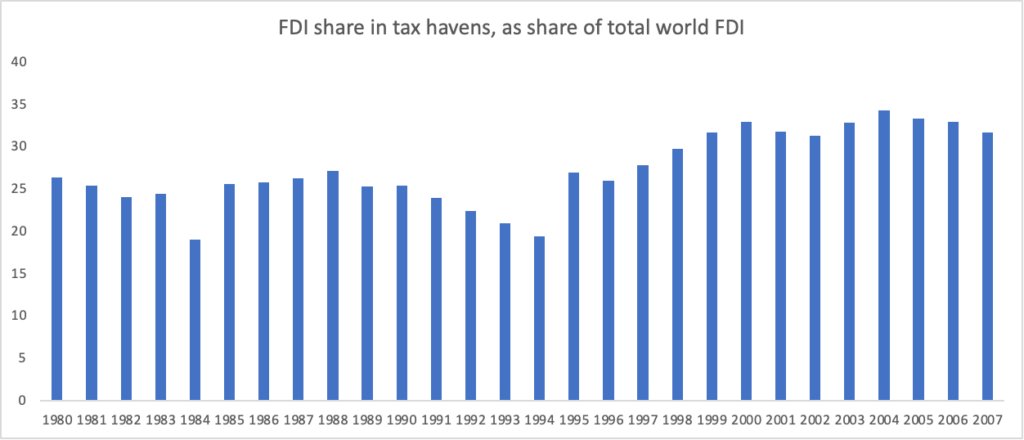

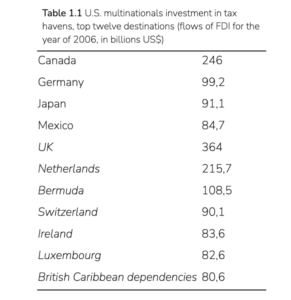

It should be noted that once funds reach the Sink OFC, they do not necessarily remain there. Oftentimes these funds are reinvested into other ventures, while the ownership remains incorporated in the Sink OFC. In fact, Sink OFCs are often utilised in foreign direct investment (FDI). For example, Mauritius, a popular Sink OFC amongst southeast Asian and African economies, has emerged as the largest foreign investor in India, with double the USA FDI in India. Fiscal economists claim the reason for this is the presence of tax treaties between India and Mauritius. It is estimated that approximately 30% of all foreign direct investment (FDI) is invested, or at the very least passes, through tax havens.

The Significance of OFCs – The Statistics and Facts

Despite recent media scandals like the Pandora Papers or Panama Papers, the general public’s understanding of the offshore world appears to be limited. The media portrayal of OFCs and tax havens is usually that of some tropical island somewhere in the Caribbeans where only mafiosi and narco barons stash their ill-gotten wealth. While that caricature can sometimes be true, it is only a small element of the larger interconnected OFC ecosystem. In reality, the largest OFCs tend to be western nations or jurisdictions very closely linked to them (historically or politically), and the biggest users of OFCs aren’t individuals, but rather multinational corporations. Furthermore, OFC specialisation and use cases vary significantly and hence cannot be easily generalised or unified under a single definition. This makes addressing negative corporate behaviour such as flight capital, tax evasion and regulatory arbitrage much harder to tackle and address.

Broadly speaking, the financial industry can be separated into retail banking and wholesale finance. Retail banking, also known as personal or consumer banking, refers to services banks offer to the general public, while services offered to wholesale banking and finance concern larger economic players, usually institutions such as corporations, banks, and hedge funds.

Intangible property/incorporeal assets tend to be highly mobile, the trade of which allows wholesale finance to enjoy flexibility to a greater extent relative to other industries. For example, a large financial institution such as a hedge fund or a bank, located in some traditional financial centre such as London or New York can have their analysts arrange financial transactions from their respective location, but “book” them through an OFC such as the Cayman Islands. Subsequently, this decreases the transaction’s exposure to taxation and regulation.

A large portion of bank branches in OFCs are mere “shell” operations, where their existence is only established on paper, with no substantial business or assets in the specified jurisdiction. As it happens, these tax haven locations very frequently compete on creating business-friendly environments to maximise the amount of mobile capital they can capture. On their own, these locations have low economic activity relative to the amount of capital present.

MNEs very frequently have complex corporate structures, involving subsidiaries, partnerships, and sub-contracted firms, all in different jurisdictions, through which they tend to do their business. Taxes on profits are commonly paid in the location where they were made. This creates an incentive to “book” transactions in OFCs, where regulations and taxes are substantially lower.

For multinational insurance giants, tax havens have become a popular destination, in what can be described as the perfect example of regulatory arbitrage. These MNEs establish “captive insurance” firms as subsidiaries in OFC locations, in order to reinsure and hedge the parent firm against risks they’ve underwritten by being exposed to lower regulatory reserve and capital requirements.

Starting in the 1980s, as the cost of litigation in the United States began to soar in conjunction with larger penalties for companies found engaging in polluting activities, such as using toxic materials like asbestos. Following this, Bermuda was the first to seize the opportunity and created a new industry in catering to insurance firms. Other tax havens followed suit. The number of “captive insurance” firms has passed more than 5,000 globally, which affects more than USD 20 billion in insurance premiums and more than USD 50 billion in assets. These days, American MNEs prefer the Isle of Man, Bermuda and the Cayman Islands for reinsurance, while European MNEs tend to go to Guernsey.

An IMF report from 1994 estimated that more than half of cross-border lending was done through OFCs (Cassard, 1994). This notion is further supported by findings from the Bank for International Settlements (BIS). Their data on international assets (mainly bank loans and obligations), as well as liabilities (primarily deposits, shares and obligations) show that banks had an estimated 51% of their cross-border assets and liabilities in OFCs in 2007. This is a fall from 65% in 1980, but still a staggering amount, as at the time, the global cross-border lending market accounted for $24.5 trillion, meaning around 12.2 trillion was affiliated with OFCs and offshore banks. Similarly, BIS also estimates that offshore banks received around 47% of all cross-border deposits and around 43% from other tax haven locations. It should be noted that BIS does not distinguish between OFCs and tax havens, meaning hubs such as NYC or London contribute to the calculation. This only goes to show the extent of how integrated the global banking and financial systems are, and how central OFCs are to it all.

It is estimated that around a third of the global GDP, and more than half of monetary stock flows pass through or concern tax havens one way or another. The Cayman Islands alone received around USD 800 billion from wealthy American individuals and corporations, which when quantified, would represent around one-fifth of all bank deposits in the United States. In 1998, the UK Home Office claimed OFCs hosted around USD 6 trillion, which at the time was ten times more than the value of all stocks listed on the London Stock Exchange. Through the use of shell companies and secrecy laws in many of these tax havens, the true owners of these assets were never known. To address this, a law requiring people to state the ultimate beneficial owners was passed, but experts say, new schemes for retaining anonymous ownership of assets appeared. Experts estimate that using OFCs allows MNEs to avoid paying anywhere between USD 50 and USD 200 Billion worth of taxes in the EU and around USD 130 billion in the US.

Conclusion

OFCs are an important tool for MNEs, allowing them to establish economically efficient corporate structures in short periods of time. This source of efficiency stems from decreased costs, thanks to regulatory arbitrage and competitive tax rates, allowing firms to grow larger, access more markets and enjoy larger profits. These incorporations can also help set up a global presence and give access to currency markets and developed financial infrastructure, allowing firms to do business at a faster rate. On the other hand, OFCs help corporations gain a competitive advantage not enjoyed by smaller domestic businesses. OFCs allow corporations to leverage themselves more from governments, protect their assets to a higher degree and pay much lower if any tax rates than smaller economic agents. Furthermore, they give room to tax evasion and flight capital which limits policy making capabilities of a country and as a result weakens the government structure. For example, should the government implement policies such as increasing taxes to fund education and healthcare, corporations could simply leave and incorporate their business elsewhere.

As it so happens, the average taxpayer is usually burdened to cover these missing tax deficits, essentially further burdening the middle and working-class citizens, while allowing the richest economic agents i.e corporations to get richer. While policymakers do make efforts it is still an ever-present challenge.

Despite the large economic role of OFCs on the global economic stage, their importance is understated in economic theory. Arguably, if we wish to understand international economics and globalisation then we need to have an understanding of OFCs. After all, understanding Conduit and Sink OFCs allows us to understand capital flows and cross-border financial transactions.

Given the complexity of international trade and differences in tax and corporate laws, policies addressing tax evasion are no easy feature, and policymakers are faced with the difficult dilemma of creating a business-friendly environment and on the other hand, implementing policies that tackle tax evasion and unfair business incorporation without causing political conflicts with other nations and not alienate themselves from the global economy.

This article is in no way advocating any point of view, nor is it meant to demonise economic agents utilising OFCs. Arguably, profit maximising nature can be explained with traditional microeconomic theory. This article merely aims to continue the discussion of OFCs and display their arguably under-reported impact on the global economy.

Yuriy Bedenko

Author

2 Responses

Roman Zalutin !

Great insights and perspective !